Theses on Feuerbach

The Germ of a New World Outlook

[illustration by sandi falconer]

“...in an old notebook of Marx’s I have found the eleven theses on Feuerbach […]. These are notes hurriedly scribbled down for later elaboration, absolutely not intended for publication, but they are invaluable as the first document in which is deposited the brilliant germ of the new world outlook.”1

Introduction

Theses on Feuerbach is a collection of eleven observations and although brief, they reveal a great deal about Marx’s method when understood in their historical context. The goal here is an introductory essay that will avoid wading too far into Hegel, the Hegelians, and the eventual debates generated by the Theses (see Althusser), although we will touch lightly on some of this; it will be just enough to set up the Theses for an introductory understanding. Ultimately, we will see how these eleven observations bridge the gap between abstract philosophy and social action.

Historical Context

In February 1845, Karl Marx was a twenty-seven-year-old without a country.

Driven out of France by Prussian diplomatic pressure, he landed in Brussels with little more than the cash from his furniture sale in Paris and a meager advance on a book deal. His wife, Jenny, joined him a few days later, first daughter in tow and pregnant with their second child. Marx rarely enjoyed stability throughout his life, but this period was especially precarious.2

Beyond financial strain, Marx also faced legal constraints. The Belgian authorities, wary of his reputation and pressured by Prussian police, forced Marx into a corner. To stay, he had to sign a formal pledge to abstain from all political activity. He also presented a contract for a work titled Critique of Politics and Economics (a project he would eventually abandon as the demands of the communist movement and his own shifting theories took over). This was a period of intense intellectual friction; Marx was no longer interested in just arguing with other philosophers; he was looking for a way out of the “pauper’s broth”3 of intellectual clutter. The material precarity of his own situation and the inability of pure ideas to fix it reflected the intellectual task Marx was wrestling with.

These three years in Brussels were an internal audit on Marx’s philosophical foundations; The Theses on Feuerbach, for instance, was never meant for an audience. The observations were a private break from the ghostly abstractions of his youth. This period led directly to The German Ideology, which was a massive manuscript he wrote with Engels to finally settle the bill with their old friends. When publishers rejected the work, Marx and Engels simply abandoned the pages to the “gnawing criticism of the mice.” They didn’t need the book anymore; they had achieved their goal: a clear, materialist map of how to actually change the world.4

Hegel

To understand the Theses, we must grasp the influence of G.W.F. Hegel. Hegel’s ideas weren’t just a philosophy; they were the official language of the Prussian state. If you wanted to be taken seriously as an intellectual, you had to speak Hegel.

Hegel is notoriously difficult to read, but his Dialectic can be understood through an often-used metaphor: the seed.

The Dialectic, in its most basic schema, can be understood within the thesis-antithesis-synthesis framework (terms that Hegel himself very rarely used). That is, a thesis (what is) collides with an antithesis (its opposite). The synthesis then develops out of this tension, pushing us to the next stage of argument, of thought, of historical transformation. While this is an oversimplification—as the dialectic is not a linear process—the seed metaphor helps layer on the complexity without getting too far into the Hegelian weeds.

If we think of the seed, we can see how the potential to become an oak tree—its perfected form—is inherent in the seed: what it can become is already a part of it. However, this does not mean the seed is destined to become an oak; it must interact with its external environment to realize its potential and become the oak tree. Even in its becoming, the seed remains a part of the oak tree: the potential for what we can become is already present in what we are, and even when we overcome our current state, it remains in what we become through negation and preservation.

We are not talking about oak trees though; we are talking about the unfolding of human history. For Hegel, history was moved by “Spirit” (Geist), which can be thought of as the collective and processual accumulation of human consciousness: the sum of human culture, laws, art, religion, and philosophy. Spirit (the engine) navigates history through self-awareness. It begins in a state of alienation (not knowing itself) and moves through the Dialectic to reach “Absolute Spirit” (its perfect form or the “pinnacle of reason”): it externalizes itself, reflects on itself, overcomes itself, and creates a new reflection expressed through the institutions of history.

This created a fundamental split among his followers regarding his dialectical method: The Old Hegelians focused on the end of Hegel’s system. They used his logic to argue that the current Prussian government was the final, perfect result of history, where the Spirit had finally reached its destination (it is the oak tree). The Young Hegelians argued that history wasn’t finished. They believed that because the dialectic relies on contradiction and tension, the current state and church should be criticized and overcome.

The Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians used Hegel’s method to attack the Church, believing that shattering religious illusions would cause the monarchy to collapse. But Marx saw through them. Despite their radical talk, they remained “staunchest conservatives” because they only fought against “phrases.” As Engels noted, they hid their lack of real-world action behind “obscure, pedantic phrases.”

Marx’s frustration with this group boiled over in The German Ideology. He mocked their belief that reality would collapse if people simply knocked these “chimeras” (ghosts of the mind) out of their heads. He famously satirized their “world-shattering” philosophy to a “valiant fellow” who believed people drowned only because they were possessed by the idea of gravity. According to this logic, if we could just purge the idea of gravity from our minds, we would be “proof against any danger from water.”5

Marx realized this was merely “fighting phrases with phrases.” As Bertell Ollman explains in Dance of the Dialectic, their method relied on bad abstractions: mental categories that were too narrow to grasp the material whole. If you only change the ideas in your head without changing the material world, nothing moves. For Marx, a good abstraction was one rooted in material history.6

The Theses are Marx’s formal resignation from this speculative circle. It was a declaration that the decaying “absolute spirit” must be replaced by the study of real, active people and their actual life-processes. For Marx, the goal wasn’t to win a debate; it was to understand the collective labour that actually builds the world, so that we might finally learn how to reclaim it.

Ludwig Feuerbach

By 1841, Ludwig Feuerbach had become the most influential figure among the Young Hegelians. He achieved this by “inverting” Hegel in his critique of religion. Feuerbach argued that Hegel had the world upside down: it wasn’t Spirit creating humanity, but humanity’s creation the idea of Spirit. For Feuerbach, God was simply a projection of human qualities: our own best traits, like love and knowledge, alienated from us and placed in the heavens.

While this resonated with Marx, it would be a mistake to think that Feuerbach introduced Marx to materialism. His own materialism already ran deeper, stretching back to his doctoral thesis on the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. As John Bellamy Foster has shown, Marx was fascinated by the Epicurean “swerve” (clinamen). In a world of atoms falling in a straight line, the swerve introduced a sudden departure from linear movement, providing an “essential basis for a conception of human freedom.” This meant that humans weren’t victims of mechanical fate; rather, we could “initiate our own actions” and change our trajectory.7 Marx’s materialism was not mechanical and was not deterministic.

Feuerbach seemingly pulled Marx down from the Hegelian clouds to the material earth, but once they landed, Feuerbach stood still. Marx realized that although Feuerbach correctly identified that humans created God, he couldn’t explain why they felt the need to do so in the first place. For Marx, the answer lay not in theology, but in the social conditions that made such illusions necessary.

Marx saw what Feuerbach missed: the “real world” isn’t just a collection of biological facts, but a site of struggle. For Marx, the material world wasn’t something to just be contemplated or “inverted” in a book; it was a relationship that had been severed and needed to be fought for.

Although it is outside the scope of this specific essay, academics like Todd McGowan have argued that Hegel was largely misread by both the Old and Young Hegelians, including Feuerbach and Marx, but the above at least outlines how they understood, correctly or incorrectly, Hegel.8

Theses on Feuerbach

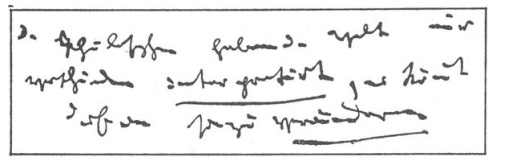

[ The 11th Thesis: image take from McLellan’s biography of Marx]

The Theses reveal how Marx maintained Hegel’s method while stripping away the “Spirit” talk. He kept Hegel’s “engine” but changed the fuel, so to speak. As it is commonly explained, Hegel argued that ideas (Spirit) formed the material world. For Marx, the material world (the material conditions of production) drove ideas.

Understanding these eleven entries is a solid starting point for understanding what Marx would later write in Capital. You can think of the Theses as a primer on Marx’s materialism. They are not just philosophical observations; they are a manual for breaking through a reified reality (reification is the process of treating a social relationship as if it were a fixed, physical object). Because these notes are brief, we can easily go through them all here.9

THESIS 1: The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism – that of Feuerbach included – is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation, but not as sensuous human activity, practice, not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was developed abstractly by idealism – which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such.

Feuerbach wants sensuous objects, really distinct from the thought objects, but he does not conceive human activity itself as objective activity. Hence, in The Essence of Christianity, he regards the theoretical attitude as the only genuinely human attitude, while practice is conceived and fixed only in its dirty-judaical manifestation. Hence he does not grasp the significance of “revolutionary”, of “practical-critical”, activity.

Marx begins with a jab at both sides. Old materialists viewed the world as a collection of static “things” to be observed, totally ignoring the human labour that produced them. Conversely, the idealists understood “activity” but kept it in the clouds of abstract ideas.

The Point: When you view a “thing” (e.g., like a smartphone or a factory) in isolation, it becomes “reified.” It looks like a natural object that just exists. Marx introduces Praxis: the idea that you cannot understand a thing without understanding the doing. To change a social relation like Capital, you can’t just think it away; you have to engage in the physical struggle that created it in the first place.

THESIS 2: The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth — i.e. the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking in practice. The dispute over the reality or non-reality of thinking that is isolated from practice is a purely scholastic question.

Marx is calling out the pointlessness of academic philosophy. Arguing about whether the world “really” exists or if an idea is “true” in a vacuum is just noise.

The Point: A philosopher must prove the “this-sidedness” of their thinking in practice. If your theory doesn’t help you understand and change the world you actually live in, it is irrelevant.

THESIS 3: The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice.

This is a strike against elitist “saviour” complexes. Many reformers believe they are enlightened observers standing outside society, waiting to fix the “passive victims” below them.

The Point: There is no “outside.” We are not just products of our environment; we are the ones who create that environment. We change ourselves precisely as we change society. The “educator” must also be educated by the struggle. Marx calls this revolutionary practice: the moment when changing circumstances and changing oneself coincide.

THESES 4 & 5: Feuerbach starts out from the fact of religious self-alienation, of the duplication of the world into a religious world and a secular one. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis.

But that the secular basis detaches itself from itself and establishes itself as an independent realm in the clouds can only be explained by the cleavages and self-contradictions within this secular basis. The latter must, therefore, in itself be both understood in its contradiction and revolutionized in practice. Thus, for instance, after the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be destroyed in theory and in practice.

Feuerbach, not satisfied with abstract thinking, wants contemplation; but he does not conceive sensuousness as practical, human-sensuous activity.

Feuerbach correctly noted that humans created God. But he stopped there. Marx asks the revolutionary question: Why?

The Point: People project their best qualities into the “clouds” of religion because their life on the ground is broken. You don’t end religious alienation by telling people God isn’t real; you end it by fixing the social contradictions that make God a necessary illusion.

THESES 6 & 7: Feuerbach resolves the religious essence into the human essence. But the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual.

In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.

Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence, is consequently compelled:

To abstract from the historical process and to fix the religious sentiment as something by itself and to presuppose an abstract – isolated – human individual.

Essence, therefore, can be comprehended only as “genus”, as an internal, dumb generality which naturally unites the many individuals.

Feuerbach, consequently, does not see that the “religious sentiment” is itself a social product, and that the abstract individual whom he analyses belongs to a particular form of society.

Feuerbach treated “the human” as a static and isolated individual.

The Point: What we call “the individual” is actually a intersection of social relations. You are a product of your class, your labour, your technology, and your history. If you change those relations, the “essence” of the person changes. Given this, there is no such thing as “natural greed,” only social systems that reward it (the material conditions).

THESES 8, 9, & 10: All social life is essentially practical. All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the comprehension of this practice.

The highest point reached by contemplative materialism, that is, materialism which does not comprehend sensuousness as practical activity, is contemplation of single individuals and of civil society.

The standpoint of the old materialism is civil society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or social humanity.

“Civil society” is the world of the isolated individual in the marketplace. From that narrow perspective, the market feels like an unchangeable law of nature.

The Point: When we stop looking at ourselves as isolated atoms and start seeing our collective existence, we move toward Social Humanity. We realize our “private” interests are actually part of a massive, interconnected system of labour.

THESIS 11: The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

This is Marx’s formal resignation from the ‘all talk’ club.

The Point: This isn’t a call to stop thinking; it is a realization that action is a form of sight. Some truths are invisible to the spectator. You can study the “theory” of a strike for years, reading every book on labour law, but you will never understand the reality of class power until you are standing on a picket line. The “truth” of that power only manifests when it is practiced. By attempting to change the world, you “defrost” the status quo, proving that what seemed like an unchangeable law of nature was actually just a social habit we can break.

Conclusion

In these short notes, we can see the blueprint for everything that follows in Marx’s thought. We see his Historical Materialism, looking at how the practical ways we feed, clothe, and organize ourselves dictate who we become. We see the Dialectic in action: as the friction between our ideas and our physical struggles.

Most importantly, Marx reveals that we are not isolated pockets of consciousness. Through what Ollman calls the Theory of Internal Relations, he shows us that what we call “the individual” is actually an ensemble of social relations. We are tied to the farmer, the factory, the landlord, and the state by invisible threads that connect us in a system of exploitation. Labour, the market, authority, money, clothing, beer, struggle: these are all things that can only be understood fully within the specific social relations they are dynamically connected to.

This realization is the “revolutionary thread” of the Theses. If we are the product of our social relations, then to change ourselves, we cannot simply “think” differently or “self-actualize” in a vacuum. We must change the world that produces us. We must identify the sources of power and dismantle them. Philosophy is no longer a hobby; it is a call to revolutionary practice.

Before ending, I think it is important to clear up a major misunderstanding: Marx’s method was never meant to be predictive. Marx wasn’t looking for a law of history that would predict the future with the certainty of physics; rather, he was looking for a way to better understand the world so that we could be better equipped to change it.

Frederick Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy (International Publishers, 1941), 8.

David McLellan, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought (The Macmillan Press LTD, London, 1973), 138-139.

Engels, Feuerbach, 7.

Ibid, 7-8

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology (Progress Publishers, 1968; Marx/Engels Internet Archive, 2000), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_The_German_Ideology.pdf.

Bertell Ollman, Dance of the Dialectic: Steps in Marx’s Method (University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 2003), 62-63, 74-75.

John Bellamy Foster, Breaking the Bonds of Fate (Monthly Review Press, New York, 2025), 81.

McGowan suggest Marx’s “rejection” of Hegel was actually a ‘productive misunderstanding’. Marx wanted to flip Hegel’s idealism onto its materialist feet, believing “Spirit” was just a religious phantom. McGowan argues that Hegel was a materialist all along. “Spirit” is just the name for our ‘collective, messy, and contradictory human activity’. McGowan also argues that by seeking a future society where social contradictions are finally resolved, Marx actually retreated from Hegel’s more radical insight: contradiction is inescapable and is the engine of freedom and existence itself. Personally, I don’t feel the need to dive too far into these arguments here. As someone who found his way to Marx through my own working class challenges and not the academics, I don’t find McGowan’s arguments all that helpful. I tend to perceive McGowan, despite enjoying his accessibility and writing, in the way that I imagine Domenico Losurdo or Gabriel Rockhill might. If this interests you though, see Todd McGowan, Emancipation after Hegel: Achieving a Contradictory Revolution (Columbia University Press, New York, 2019), and Todd McGowan, Embracing Alienation (Repeater, London, 2024)

I accessed Theses on Feuerbach via The Marxist Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm

Thank you so much for this. I had not read the Theses. Your writing on Marx is so clear.

Excellent piece! Thank you for writing it